the Woman's Building

The Woman's Building, L.A. 1973 - 1991

An Essay by Terry Wolverton

From a slide lecture presented at the 15th Annual California Studies Conference at UC Davis, April 2003.

Feminist art raises consciousness, invites dialogue, and transforms culture.

- Arlene Raven, art historian and Woman's Building co-founder

Last spring, while attending a writing conference in the desert, I had occasion to share a table over lunch with a woman I'd never met before. Perhaps ten years my senior, she confided that she was back in school pursuing her doctorate. Her dissertation, she divulged, would be about representations of Eve in the work of contemporary writers and artists.

"I have a poem with Eve in it," I couldn't help but offer, and she insisted I send it to her.

Like me, she was a feminist, and it was through this door that we entered to find common ground. Our conversation was deep and intimate, rapid fire, ideas and revelations spilling over themselves in our fervor to express them. Amidst the sea of writers and academics at the conference, we were delighted to have found each other.

Truth is, for that hour or so over salad and sandwich, I think we fell a little in love with each other. I don't mean that in the romantic sense. I was reminded of the early years of Second Wave feminism, the seventies, when women were becoming conscious of our own power and vibrancy, and when we'd meet another who was engaged in that same process, we couldn't help but fall in love because she was a reflection of our own possibilities.

So I was startled when, near the end of our meal, my table companion lamented, with great sorrow and weariness, that the women's movement had been "a failure."

"How can you say that?" I asked, incredulous.

"Well, so much of what we fought for didn't come to pass," she explained.

"But so much has! Don't you remember what it was like before?" I pleaded with her. "In the nineteen sixties, would you have imagined that you could get your Ph.D.? Could we have regarded Eve as anything other than the source of original sin? We have to measure our success from where we've come, not by how far we have to go!"

Breathless, I made myself stop; I was in danger of spontaneous combustion. Yet, here we were: two women writers engaged in passionate discourse about ideas we held dearest: our work, our inspiration, our identities as women. Without the women's movement, and for myself, specifically without the feminist art movement, I knew, we would not have been there.

To understand the origins of the feminist art movement in the United States, one must look to the foment of the 1960s and early 70s, the swarm of rebellion and leaps in consciousness that redefined American culture. In 1955 a seamstress named Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama bus and thus gave rise to the Civil Rights Movement, which ignited a host of struggles for social liberation waged by women, Chicanos, Native Americans, gays and lesbians, and others. These movements not only demanded more equitable distribution of power and resources, but raised profound questions about the meaning assigned to these identities and the cultural representations of these groups.

Opposition to U.S. involvement in Vietnam stoked an unprecedented youth movement which, in addition to the politics of protest, embraced "sex, drugs, and rock 'n roll." This fueled a thriving counterculture determined to forge alternatives to the economic, social, and moral structures of the mainstream.

Within the art world, too, there began to be a challenge to the hegemony of formalism that had dominated the 1950s and '60s, in which any concern for content in art was disregarded or disdained. Questions of cultural identity incited a push for the democratization of art, a demand for greater inclusiveness with regard to both who could make images and who had access to them.

The feminist art movement in California began in 1970, a year which saw the protest by women artists of the "Art and Technology" exhibit at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in which not one woman artist was included. Further research uncovered the statistic that of eighty-one one-person shows at LACMA in a ten-year period, only one presented the work of a woman artist. That same year, artist Judy Chicago established the Feminist Art Program at California State University, Fresno. These two events serve to illustrate the dual concerns of the feminist art movement: the push for better inclusion of women in the mainstream art world and the utter redefinition of art and culture within a feminist context.

In 1971, Judy Chicago moved the Fresno program to California Institute of the Arts (Cal Arts). With the school still under construction, the twenty-five students of the Feminist Art Program launched a large-scale, site-based, collaborative project, "Womanhouse," spearheaded by Chicago and her colleague, artist Miriam Schapiro. Working together, they transformed the rooms of a slated-for-demolition Hollywood mansion into art environments that eloquently protested the domestic servitude of women's lives. In "Breast Kitchen", for example, the all-pink walls and ceiling were affixed with fried eggs-sunny side up-that gradually morphed into women's breasts, a trenchant comment on women's role as nurturers. "Fear Bathroom," contained the plaster figure of a woman in the tub, frozen up to the neck in cement, and addressed the state of confinement and paralysis felt by women. "Linen Closet" displayed the torso of a female mannequin segmented by the closet shelves. This latter image was reproduced in Time magazine; "Womanhouse" was, without question, the most publicly visible work of feminist art to date.

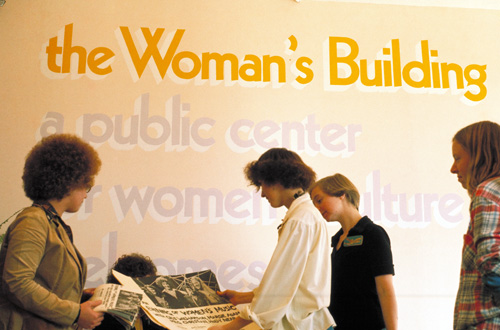

The Woman's Building, on which this presentation centers, attempted to walk the line between the movement's dual concerns, calling itself "a public center for women's culture." Founded in 1973 in Los Angeles by Judy Chicago, graphic designer Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, and art historian Arlene Raven, the Woman's Building offered opportunities for women in the fields of creative writing, graphic design, the printing arts, performance art, video, and visual arts. "Public center" signified the wish to make a place for women artists in the mainstream, while "women's culture" revealed more subversive intentions. Women live in a different culture than men, was the claim, bounded not only by social position and opportunity but also by differing concerns, values, and worldviews. In 1973, when the Building was founded, we were arrogant enough to try to codify those differences, blithely secure in the assumption we could speak for all women. The later 70s and especially the 1980s would foreground pervasive differences among women-including race, class, and sexual orientation-and the pitfalls of essentialism.

The initial vision of the three founders, all of whom had been on the faculty of California Institute of the Arts, was to create an alternative program for women's art education, the Feminist Studio Workshop (FSW). But de Bretteville, especially, did not want to replicate another ivory tower, and sought to align this new school with the burgeoning women's movement in Los Angeles. Out of this expansive vision was formed the Woman's Building , a public center that could house the school as well as other feminist organizations and businesses.

Frontice piece from the catalog for the 1893 exhibition. Woman's Building 1893

The Woman's Building in Los Angeles was named for another structure built in 1893 by architect Sophia Hayden for the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. That building, which was demolished after the Exposition, exhibited arts and cultural works by women and included a mural by Mary Cassatt.

When it opened in 1973, the Woman's Building was home to three galleries dedicated to women's art -- Womanspace, Grandview, and 707. Sisterhood Bookstore sold feminist and non-sexist literature and music. Three women's theater groups-the L.A. Feminist Theater, the Women's Improvisational Theater, and the Women's Performance Project-staged productions in the auditorium. Other tenants included an office of the National Organization for Women (NOW), a coffeehouse, and Womantours, a feminist travel agency.

Still, its principal program was the Feminist Studio Workshop (FSW.) At a time when the mainstream art world was primarily concerned with forms and surfaces, the Feminist Studio Workshop offered a wholly different set of questions: "What is it you want to say as an artist, and to whom do you wish to say it?" Participants were encouraged to create work inspired by their life experience. Critiques were focused not on what was "wrong" with the work, but on what message the work was communicating, and how that might be accomplished most effectively.

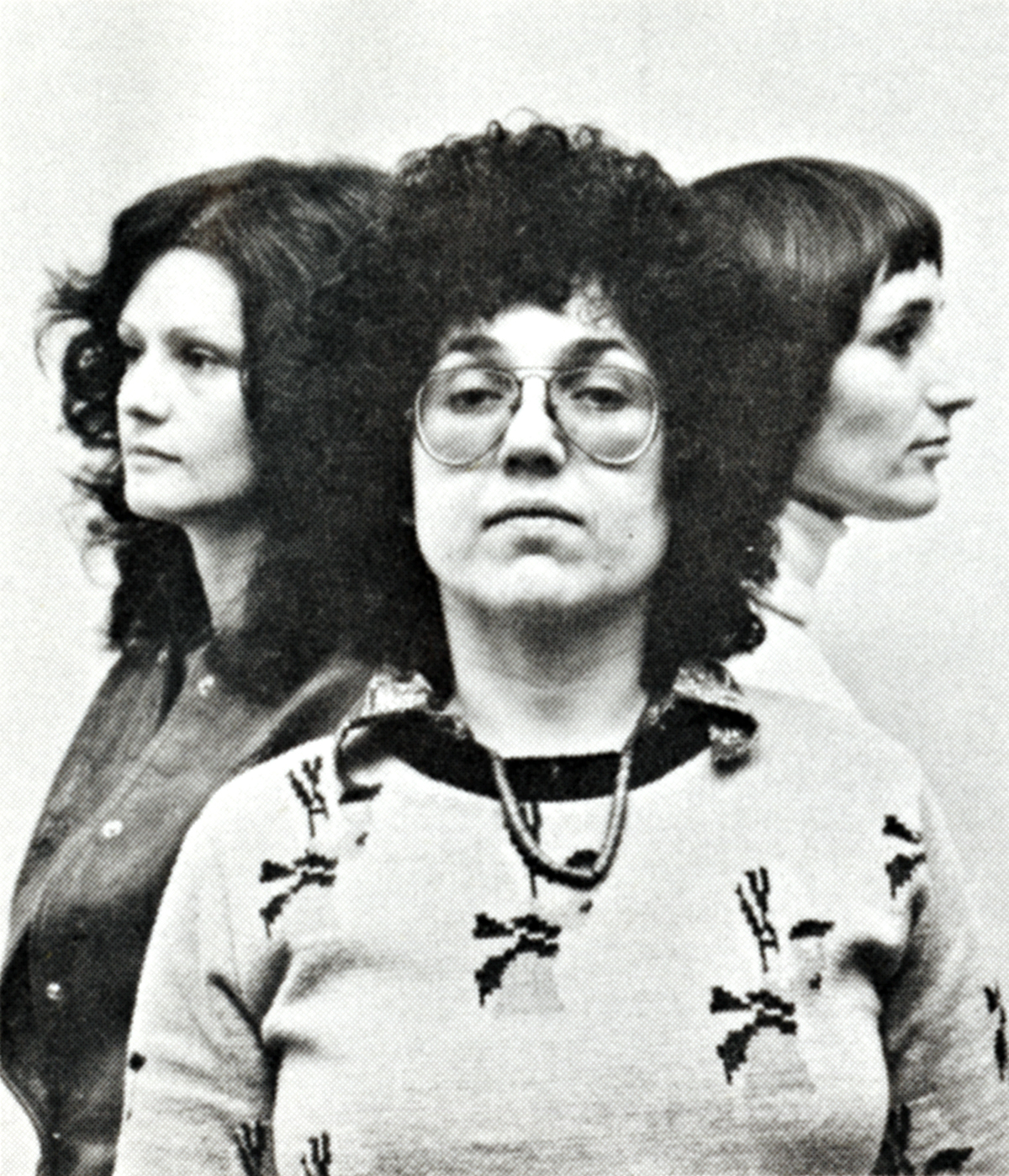

Between 1973 and 1981, women from across the country and from around the world moved to Los Angeles to participate in the two-year program of the FSW. Some of these women went on to become established artists in their own right; a number of them also became responsible for the operations of the Woman's Building.

The FSW closed its doors in 1981, victim of economic shifts and the sea change in social attitudes that followed the election of President Ronald Reagan. Still, the Woman's Building continued until 1991 to offer opportunities for artmaking, exhibition, and education for women artists.

I spent thirteen years-from 1976 to 1989 at the Woman's Building, beginning as a student in the FSW, then becoming a teacher, program director, exhibiting artist, publicist, typesetter, newsletter editor, grantwriter, board member, development director, and eventually, executive director. I washed dishes and painted walls, and sorted bulk mailings, and hauled enough folding chairs for a few lifetimes. While I was not there at the founding, I did experience some of those brazen, heady days of the 1970s when we were convinced we would change the world. I lived through the years of backlash, when we struggled to maintain our values in the face of economic hardship and a hostile political climate. I was witness to its eventual demise, the final succumbing-as with all utopian experiments-to inevitable change that rendered, if not its vision, then the manifestation of its vision obsolete. And I mourned it for years after, inconsolable, the way one grieves for a lost mother.

For those thousands of women, the Woman's Building provided an unparalleled opportunity: to experience oneself as both woman AND artist, and to explore the potential significance of those intertwined identities in a context in which the value of such investigation was understood. Without this context, one is left to face alone the oppression any artist confronts-indifference, hostility, suspicion, self-doubt. Add to this the baggage of sexism, the inclination to question whether a woman is entitled to express herself at all, and in which ways, and to whom, and about what, and with what reward.

The Woman's Building provided a community in which a woman was encouraged not only to speak, but to find her authentic voice and cultivate an audience eager to hear it. Keeping alive that vision that it may seed future endeavors of its kind-in other forms, at other times and places-is the purpose of my book, Insurgent Muse: Life and Art at the Woman's Building, a memoir published in 2002 by City Lights Books.

In 1970, Judy Chicago founded the first feminist art program in the country at California State University, Fresno in 1970. That first year, Judy Chicago's visionary Feminist Art Program drew fifteen women students, many of whom were new to both feminism and artmaking. Still, it was from the work of this initial group of participants that many of the core principles of feminist art education evolved. These concepts would guide Chicago and her colleagues when they established the Feminist Studio Workshop in Los Angeles three years later.

It was in the Fresno program that women first employed the process of consciousness-raising in the classroom, Consciousness-raising, or C-R, is a communication process in which women sit in a circle and each takes equal time to speak, uninterrupted, about her experience while the others listen attentively. C-R sessions are usually directed to a specific topic, such as body image, mothers, etc. The practice allows an individual to validate her experiences and to probe their meanings; it also encourages women to see the commonality of their experiences, to realize that some problems have social, not personal, causes.

The slogan "The personal is political" is rooted in the C-R process. It is crucial to remember that in the early days of feminism, most women rarely considered the events of their lives to be worth mentioning, to have any significance at all. C-R was adapted by North American feminists from a practice called "speaking bitterness," used by women in revolutionary China. Feminist artists used C-R both to understand more deeply their position as women and to generate material for their art. This strategy flew in the face of the art establishment; in 1970, women's experience was considered trivial and frivolous, unsuitable as subject matter for creative work. Indeed, since the end of World War II, narrative content had become taboo in the New York art world; formalist concerns dominated the critical discourse. Serious art was, by definition, the province of men, and if a woman hoped to pass into this hallowed terrain, she could only do so by making herself as much like a man as possible. The rare female art student who called attention to her gender by daring to create a work that referenced menstruation, marriage, motherhood, or household drudgery could fully expect to be criticized or mocked by her male instructors.

In order to create an environment in which women could explore their lives through art, participants in the Fresno program insisted upon a separate classroom environment for female art students, one in which women could create the context and control what happened there. Such separation would provide not only protection from corrosive or undermining feedback, but also allow women to bond with one another and to define for themselves their paths as artists. Additionally, the women of the Fresno program asserted the importance of female role models, both in being instructed by women and in studying the long-buried history of women's art. Finally, Chicago and her students openly challenged the notion of art as a work of individual genius by engaging in collaborative creations.

Art historian Arlene Raven had joined the faculty of the Cal Arts Feminist Art Program, and graphic designer Sheila Levrant de Bretteville established the Women's Design Program at Cal Arts as well. In conversations with Chicago, they shared their frustrations about working within a male-dominated institution. Separate classes for feminist students could only be so effective, they observed; what went on in those classrooms was too easily dwarfed by the larger context. They would routinely spend their class sessions building up the confidence of women students, encouraging them to take risks, only to see those same students' work disparaged or dismissed by male instructors.

In 1973, Chicago, de Bretteville, and Raven made the decision to leave Cal Arts to found an independent school for women in the arts, a place where students could explore a feminist vision of their work and gain authority and power within that vision. The Feminist Studio Workshop (FSW) opened in September. Initial class sessions were held in de Bretteville's living room, but by the end of November the FSW was installed in the building that had once housed the old Chiounard Art Institute on Grandview Boulevard.

As a young design student, Sheila de Bretteville had been fascinated with the Bauhaus movement and, later, by utopian experiments in Italy and Scandinavia that utilized principles of architecture and design to construct new models of community, new structure for social relations. The FSW was intended to be a community for its participants, and de Bretteville argued that their new school should not be isolated from the life of the burgeoning feminist community in Los Angeles.

The Woman's Building was born of this intention and became the hub of a rare synthesis between cultural, political, social, and entrepreneurial strands of feminist Los Angeles. In the spring of 1975, the Woman's Building hosted a series of groundbreaking conferences on feminist design, performance, film and video, ceramics, and writing. Hundreds of women gathered to listen as Kate Millett, Meridel LeSeuer,and others spoke about the new directions feminists were forging in the arts.

The Woman's Building moved to a new location in the fall of 1975; some, but not all, of its original tenants came along.

FSW students were predominant among the small army of women who hammered sheet rock and sanded floors, renovating the new building for its grand opening. Actress Lily Tomlin and feminist singer Holly Near headlined the gala opening event.

It was to this location that I came in 1976 to become a student in the Feminist Studio Workshop.

Within the history of art, woman searched in vain to find ourselves reflected in the mirrors of culture. What did we find? Dull-eyed beauties whose gaze evaded ours; mounds of flesh arranged like bowls of voluptuous fruit; evil temptresses, corrupters of men. More often, we found nothing at all, a curious silence. Culture proved to be a funhouse mirror, distorting and diminishing, a surface into which we walked and then disappeared.

I have mentioned earlier that one of the goals was to create a redefinition of art and culture in a feminist context. It is also true that feminist art sought to redefine and re-imagine women within the context of culture. Feminist art became the perfect vehicle with which to question the identities that had been offered to us, to re-image women as we knew ourselves to be.

When I first arrived at the Woman's Building, I didn't understand the difference between theater and performance art. Over time, I learned that performance art sprang from an entirely different tradition-not from theater at all but from the visual arts. In the early decades of the twentieth century, artists began to question the notion of art as object, to become more interested in conceptualization than in an end product. Futurists, Dadaists, and Surrealists still made art objects, but appreciation of these was enhanced by knowledge of the theories and processes that gave rise to them. In the 1950's, the "action painters" emerged; their focus was on the process of applying paint to canvas-throwing or spilling paint, or covering their bodies with pigment and rolling across the canvas. It was in the gesture of painting, they believed, that art resided, more than in the product that resulted. By the 1960s, the Fluxus artists had coined the term "conceptual art," declaring that art resides in its ideation. Some artists simply typed up their ideas on 3x5 cards.

Yoko Ono published a book, Grapefruit, containing page after page of ideas for possible performance actions. It was enough for the audience to imagine the concept; actually manifesting it was beside the point. Some posited that-just as a painter or photographer might frame a landscape or a scene-an artist could put a frame around some aspect of experience, whether an instant or a prolonged span of time, and declare that the work of art.

While some artists framed everyday experiences (in a performance created for Womanhouse, artist Karen LeCoq sat before a mirror, repetitively applying and removing make-up), others set about to concoct an experience that might not have otherwise happened, and thus impact directly the lives of their audience. Artist Joy Poe staged her own rape during an opening at Artemesia Gallery in Chicago, creating a moral dilemma for her viewers: should they intervene against this crime and risk disrupting "art," or should they remain passive spectators and in doing so, become complicit in Poe's violation? Being faced with this quandary angered many in the audience who felt entitled to a clearer delineation between art and life. Performance actions might be performed privately, as a kind of personal ritual, and later revealed to an audience through documentation-as when Linda Montano committed herself to listening, via headphones, to a single musical note, tuned to one of the seven chakras or energy centers in the body, ceaselessly for one year. Others might be witnessed only accidentally by passersby, as when Adrian Piper dressed as a man to walk around the streets of New York. Such events might take place before an invited audience which was frequently incorporated into the piece, being asked to participate either through directed action or randomly. Suzanne Lacy, for example, dressed as a vampire and spent the night in a coffin while the audience was instructed to file past and gaze, as mourners, into the open casket. Here the audience transcended their role as spectators to become performers in the tableau. Feminist artists gravitated to performance for several reasons. Both performance and video were emerging art forms in the early seventies, without established traditions or hierarchy. While it was hard for a woman painter to make a name for herself in a centuries-old tradition where men predominated, in performance a woman could get in on the ground floor. Feminists were further drawn to performance's focus on process over product, and to the form's utilization of the body as art medium. And one could use it as a means to build community, whether through collaboration with other artists or by involving the audience in direct dialogue about the issues contained within the work, C-R style.

Feminist practitioners contributed four significant elements to the medium of performance: First, an exploration of alternative personae, which was in keeping with the feminist intention to redefine roles for women. Second was the use of confessional text, which grew out of both consciousness-raising sessions and then-pioneering practices in feminist literature in which writers revealed intimate details of their lives and allowed the reader to eavesdrop on their internal monologues without the veil of fiction. Interestingly, those two directions both tended to push performance art in a more theatrical direction, as did number three: the incorporation of ritual and feminist spirituality, returning to theater's earliest roots as religious ceremony.

The final contribution made by feminists was the promulgation of performance art as media event, the creation of spectacle designed to attract the eye of the media, and thus gain a mass audience for the feminist statement being made. In 1978, Leslie Labowitz and Suzanne Lacy teamed up with Bia Lowe and other artists to create In Mourning and In Rage, a large-scale public protest performance. The purpose was to challenge the media's sensationalizing of a rash of murders of women perpetrated by the so-called Hillside Strangler; the tone of the press coverage was heightening the climate of fear and reinforcing the victimization of women. Exceptionally tall women, made taller by towering headpieces, were transported by hearse to City Hall. Dressed in black, they debarked and formed a circle in front of the steps beneath a banner reading, "In memory of our sisters, women fight back." The artists designed the performance action and imagery specifically to captivate the interest of television news and, in successfully achieving this network coverage, not only used the media to critique itself, but extended the impact of the piece far beyond the usual feminist and/or art audiences.

Even already established elements within the performance medium were altered by feminist practice. Male artist Chris Burden, for example, utilized the body as art medium by arranging to have himself shot in the arm with a pistol, then documented the experience as a performance. FSW participant Jerri Allyn, by contrast, placed a rented hospital bed in her studio and spent a week there exorcising her fear of cancer, the disease that had taken her mother's life. Viewers could attend "visiting hours" and hear Allyn read from her journals, or listen to a parade of researchers and alternative healers discuss the latest approaches to cancer treatment.

Finally, numerous women challenged the notion of the individual artist, the lone genius, by working collaboratively. Collaborative performance groups not only used a democratic process to create their work, but also sought to address an audience outside of the traditional art institutions. In "This Ain't No Heavy Breathing," the Feminist Art Workers picked women's names at random out of the phone book, and, in direct contrast to the lewd or threatening phone call, would call to tell them what strong and wonderful women they were, and wish them a good day. The Waitresses performed in restaurants to raise consciousness about the issues of working women, particularly those in service industries. Sisters of Survival donned nuns' habits the colors of the rainbow to protest the spread of nuclear arms.

This concern with democratizing audiences, and with the messages these audiences were receiving, also guided the philosophy of the Women's Graphic Center, another program at the Woman's Building. From the perspective of founder Sheila de Bretteville graphic design was all about communication. But public communication-from political speech to news reporting to advertising-seemed to be largely the province of men, while women's communication was relegated to the private sphere. The Women's Graphic Center sought to change this, both by providing women access to printing equipment (by which they could make their communications public), and with a philosophy that sought to directly undermine the schism between public and private communications. This project was frequently made explicit. Artists were invited to make posters about a specific public site, and then display their works in that site. If women came to the Woman's Building with a tendency to keep their work private, within the Women's Graphic Center they were encouraged to think about public venues for their work, such as bus posters celebrating the lives of women or postcards dedicated to female role models.

The Woman's Building. What other city but Los Angeles could have given birth to such an edifice? City of extremes, pressed against the brink of the Pacific, the endpoint of our restless explorations. City of dreams, where multitudes flock to reinvent themselves, to live out their personal myth. City that has slipped from the yoke of tradition, eluded the burden of history. City that levels and starts anew. The Woman's Building was a place.

An institution. A gathering of women. It was an eighteen-year experiment. It was a collision of history and politics and art. It was poetry, painting, performance. It was the one night you went there for a dance and it was the thirteen years you spent trying to keep it ablaze. It was the day you showed up with hennaed hair only to find that five other women had hennaed their hair the night before too.

It was the rope straining in your hands as you hoisted the ten-foot-tall sculpture of a naked female figure onto the roof of the building, from which vantage point the entire city was her domain.

It was a field of crosses planted on the lawn of City Hall by women dressed in nuns' habits the colors of the rainbow, in protest of nuclear arms. It was a wall made of bottles, a tree of dolls' heads. A circle of women who stared unflinching into the video lens and told the stories of their sexual abuse. It was the dope you smoked on the fire escape, the Friday nights you stayed late trying to figure out how to pay the bills. It was the first book you self-published on the antique printing press; it was the consciousness-raising group you hated. Language splinters under the complexity, the immensity, the tens, perhaps hundreds of thousands of women whose imaginations and emotions and lives touched and were touched by the Woman's Building. All their stories, their dreams. And it was the art that was made within its walls, yes, but also the art that was made by some woman in some little town, work that came into being because she'd heard that the Woman's Building dared to exist.

The Woman's Building offered up a spark, and this was the message in its glow: that you, a woman, could be an artist too, and that your woman's life-whatever its particulars-could kindle your art, and that in turn, the act of making art would ignite that life, and finally, that a community of women, engaged in the twin acts of making art and making a new life, would transform the mirrors of culture into windows through which you all would fly, like sparks, into the night sky.